December 19, 2014

Stanton A. Glantz, PhD

Implications of major national survey showing ecigs surpassing cigs among teens in 2014 in US

Last week, the University of Michigan released its NIH-funded Monitoring the Future survey that found that e-cigarette use had surpassed conventional cigarette youth among middle and high school students. The results appropriately received major press coverage (including US News, USA Today, NY Times) and, of course, dismissive commentaries from long-time industry apologists (example).

The results continue to contribute to the emerging picture of how the e-cigarette epidemic is developing and highlight the fact that it is necessary to keep the fact that the epidemic is still developing in mind when interpreting research results:

- Youth are responding to e-cigarette marketing and promotion more than adults are, so the fact that few nonsmoking adults are taking up e-cigarettes (at least so far), says nothing about kids.

- Because the market penetration is increasing so fast, it is important to consider when surveys were done. Every year the numbers are higher and use patterns from earlier years, especially among youth, are unlikely to reflect behavior today.

- Because market penetration seems higher among younger kids is higher, it is important to consider the age of survey respondents.

I would urge my public health colleagues who are enthusiastic about e-cigarettes as possible (but as yet unproven) cessation or harm reduction aids to think more seriously about how their enthusiasm is trickling down to kids. The MTF data (consistent with other smaller studies published earlier) that believing that e-cigarettes are healthy is a major reason for youth initiation. While there is no question that a smoker completely shifting from cigarettes to e-cigarettes will be exposed to lower levels of many toxins (but not ultrafine particles or nicotine and higher levels of smoke other toxins), a kid who would not otherwise smoke taking up e-cigarettes is going to suffer substantial negative health effects compared to a non-user.

While the precise fraction of kids who start nicotine addiction is not yet known, it is not zero. My guess is that the gateway number will be at least 30% and likely much higher. Why?

- There is a substantial (and growing) fraction of kids that initiate nicotine use with e-cigarettes.

- There are high levels of dual use; all of those kids did not start with cigarettes.

- Kids who experiment with cigarettes and use e-cigarettes are much more likely to become established cigarette smokers.

- Kids who use e-cigarettes are more susceptible to cigarette smoking.

Kids in the US and Korea who want to quit cigarette smoking are also more likely to use e-cigarettes and less likely to have stopped smoking.

One reasonable response to this picture is to enact policies that restrict sales of e-cigarettes to kids, but policymakers and advocates need to be careful to block industry efforts to use such efforts to win Trojan Horse legislation that has the effect of making it harder to enact public health policies to control e-cigarette use, particularly including them in clean indoor air laws and taxing them. (The Obama Administration should also drop the exemption for internet sales that the While House inserted into the proposed FDA deeming rule, but at the rate that the Administration is moving, public health authorities cannot expect anything of consequence on e-cigarettes from the FDA for years, well after the epidemic is fully established.)

The most important policies for localities and states to implement are

- Include ecigarettes in clean indoor air laws

- Include e-cigarettes in tobacco control media campaigns

- Prohibit e-cigarette sellers near schools and other kid-oriented places

- Prohibit the sale of e-cigarettes with flavors

- License e-cigarette sales (along with all tobacco products) and limit the number and location of outlets

The media campaigns should stress the following messages:

- E-cigarettes do not deliver "harmless water vapor"

- E-cigarettes pollute the air and non-users absorb poison chemicals that e-cigarettes put in the air

- Cigarette companies are selling the most widely promoted e-cigarettes

- Using e-cigarettes and cigarettes together (dual use) is smoking cigarettes

- E-cigarettes are not a proven way to quit smoking, particularly as used in the real world

Here is the MTF press release (December 16, 2014) A YouTube video explaining the results is here. The detailed data tables are available here.

E-cigarettes surpass tobacco cigarettes among teens

ANN ARBOR—In 2014, more teens use e-cigarettes than traditional, tobacco cigarettes or any other tobacco product—the first time a U.S. national study shows that teen use of e-cigarettes surpasses use of tobacco cigarettes.

These findings come from the University of Michigan's Monitoring the Future study, which tracks trends in substance use among students in 8th, 10th and 12th grades. Each year the national study, now in its 40th year, surveys 40,000 to 50,000 students in about 400 secondary schools throughout the United States.

"As one of the newest smoking-type products in recent years, e-cigarettes have made rapid inroads into the lives of American adolescents," said Richard Miech, a senior investigator of the study.

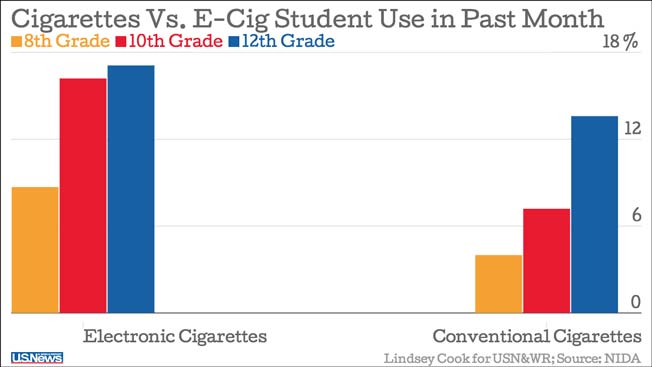

The survey asked students whether they had used an e-cigarette or a tobacco cigarette in the past 30 days. More than twice as many 8th- and 10th-graders reported using e-cigarettes as reported using tobacco cigarettes.

Specifically, 9 percent of 8th-graders reported using an e-cigarette in the past 30 days, while only 4 percent reported using a tobacco cigarette. In 10th grade, 16 percent reported using an e-cigarette and 7 percent reported using a tobacco cigarette. Among 12th-graders, 17 percent reported e-cigarette use and 14 percent reported use of a tobacco cigarette.

The older teens report less difference in use of e-cigarettes versus tobacco cigarettes.

"This could be a result of e-cigarettes being relatively new," said Lloyd Johnston, principal investigator of the project. "So today's 12th-graders may not have had the opportunity to begin using them when they were younger. Future surveys should be able to tell us if that is the case."

E-cigarettes are battery-powered devices with a heating element. They produce an aerosol, or vapor, that users inhale. Typically, this vapor contains nicotine, although the specific contents of the vapor are proprietary and are not regulated. The liquid that is vaporized in e-cigarettes comes in hundreds of flavors. Some of these flavors, such as bubble gum and milk chocolate cream, are likely attractive to younger teens

E-cigarettes may serve as a point of entry into the use of nicotine, an addictive drug. The percentages of past 30-day e-cigarette users who have never smoked a tobacco cigarette in their life range from 4 percent to 7 percent in 8th, 10th and 12th grades. For these youth, e-cigarettes are a primary source of nicotine and not a supplement to tobacco cigarette use. Whether youth who use e-cigarettes exclusively later go on to become tobacco cigarette smokers is yet to be determined by this study, and is of substantial concern to the public health community.

E-cigarette use among youth offsets a long-term decline in the use of tobacco cigarettes, which is at a historic low in the life of the study—now in its 40th year. In 2014, the prevalence of smoking tobacco cigarettes in the past 30 days was 8 percent for students in 8th, 10th and 12th grades combined. This is a significant decline from 10 percent in 2013, and is less than a third of the most recent high of 28 percent in 1998. One important cause of the decline in smoking is that many fewer young people today have ever started to smoke tobacco cigarettes. In 2014, only 23 percent of students had ever tried tobacco cigarettes, as compared to 56 percent in 1998. Of particular concern is the possibility that ecigarettes may lead to tobacco cigarette smoking, and reverse this hard-won, long-term decline.

"Part of the reason for the popularity of e-cigarettes is the perception among teens that they do not harm health," Miech said.

Only 15 percent of 8th-graders think there is a great risk of people harming themselves with regular use of e-cigarettes. This compares to 62 percent of 8th-graders who think there is a great risk of people harming themselves by smoking one or more packs of tobacco cigarettes a day.

Because e-cigarettes are relatively new, a comprehensive assessment of their health impact—especially their long-term consequences—has yet to be developed.

Tables and figures associated with this release may be accessed at: http://monitoringthefuture.org/data/data.html [emphasis added]

# # # # #

Monitoring the Future has been funded under a series of competing, investigator-initiated research grants from the National Institute on Drug Abuse, one of the National Institutes of Health. The lead investigators, in addition to Lloyd Johnston, are Patrick O'Malley, Jerald Bachman, John Schulenberg, and most recently Richard Miech—all research professors at the University of Michigan's Institute for Social Research. Surveys of nationally representative samples of American high school seniors were begun in 1975, making the class of 2014 the 40th such class surveyed. Surveys of 8th- and 10th-graders were added to the design in 1991, making the 2014 nationally representative samples the 24th such classes surveyed. The 2014 samples total 41,551 students located in 377 secondary schools.

The samples are drawn separately at each grade level to be representative of students in that grade in public and private secondary schools across the coterminous United States.

The findings summarized here will be published in January in a forthcoming volume: Johnston, L. D., O'Malley, P. M., Miech, R.A., Bachman, J. G., & Schulenberg, J. E. (2015). Monitoring the Future national results on adolescent drug use: Overview of key findings, 2014. Ann Arbor, Mich.: Institute for Social Research, the University of Michigan. The content presented here is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institute on Drug Abuse or the National Institutes of Health. This year's findings on alcohol and illicit drug use are presented in a separate companion news release: http://monitoringthefuture.org/press.html.

Add new comment